During his lifetime, the prose-writer, poet and critic Jaan Oks published his articles and short stories in newspapers and various almanacs. His period of productivity was brief as he early succumbed to a mental depression that paralysed his work. Books came out only posthumously. The most important of them are: Tume inimeselaps (An Obtuse Soul, 1918); Kriitilised tundmused (Critical Sentiments, 1918); Kannatamine (Suffering, 1920); Neljapäev (Thursday, 1920); Kogutud teosed (Collected Works, Stockholm 1957); Vaevademaa (Land of Sorrows, 1967); Hingemägede ääres (At the Hills of Soul, 1989); Emased (The Females, 1995); Ihu (Body, 1998).

He did not actually fit in anywhere, not even into Estonian literature. Was he aware of that? I think he was. Why else was he so unconcerned about himself and the others … and wrote heedlessly, Let our reviewers keep claiming for seven years that the works (my works – V.V.) have no artistic value whatsoever, on the eight they have no choice but to admit that they have. My mood can take criticism. 1908.

True enough, much is written about Oks today, more than ever before. Practically everything he wrote has been published as well.

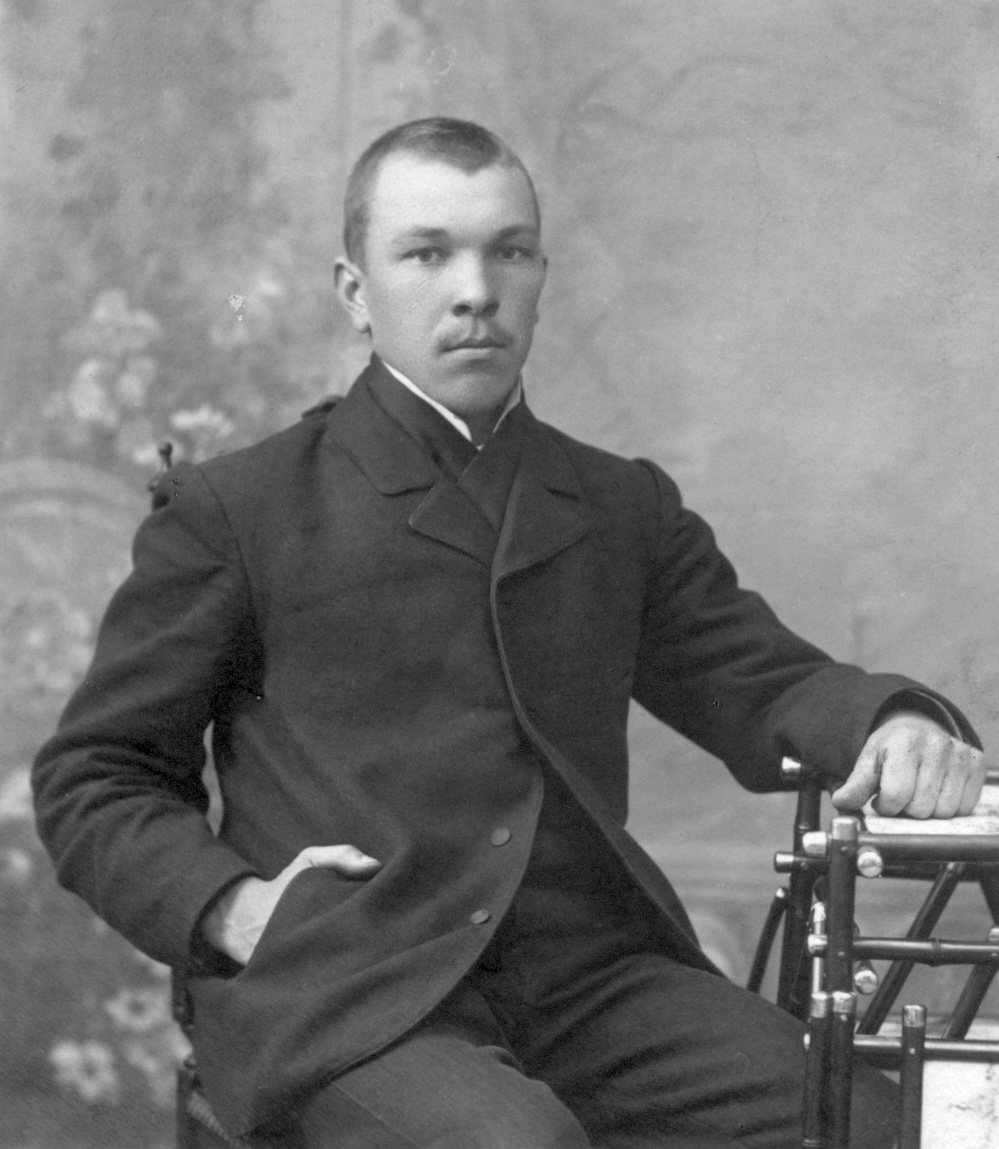

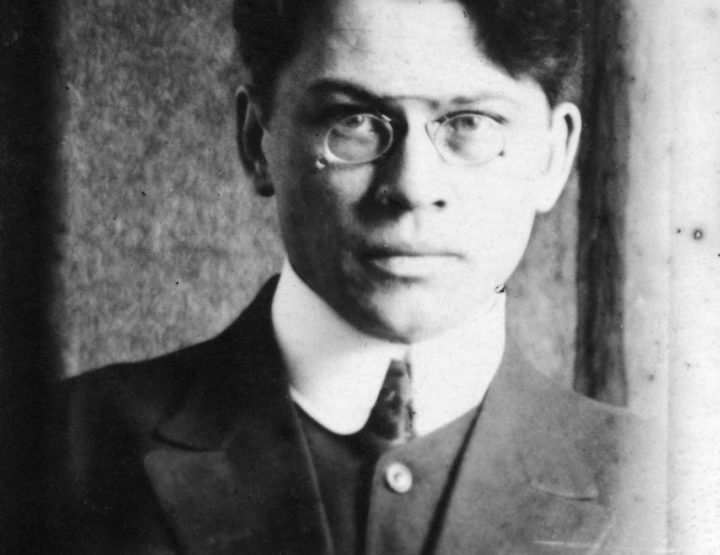

What do we know about Jaan Oks as an Estonian writer? I would say not much. Twenty years ago, on Oks’s 100th anniversary, I wrote that the writer Jaan Oks from a schoolmaster’s family on the island of Saaremaa, travelled around all his life, but not on the sea that would have been natural for an islander, but along land, along his own instinctive literary furrows. In the opinion of many readers, his furrows provided few plants. Oks craved for all sort of knowledge, but wherever he studied or worked, his main occupation was always literature. His life as a writer began when he was a schoolteacher, first in Estonia then in Russia. In 1912 he was sacked from teaching job and returned to his native Saaremaa where he whiled away time, reading the Bible, studied French and sent short articles on current news to various papers. At the outbreak of war in 1914 he was sent to the barracks in St Petersburg where he was disqualified on the grounds of poor health and odd behaviour. Having recovered a bit, he joined the construction works of the Tallinn naval fortification. There Oks worked frantically and saved money – his new passion – until May 1917 when he was hospitalised for bone tuberculosis. On 25 February 1918 he died. Nameless, with only a number (33) on the cross, he was buried in the Rahumäe cemetery. It took his brother Eduard a year before he tracked down the right place. Since 1931 a granite stone by sculptor Sannamees marks the grave.

People who have studied Oks more or less unanimously agree that the heyday of his career was between 1905 and 1909. The 1905 revolution incited Oks to take up political journalism. His articles appeared in numerous papers, depicting the miserable conditions of rural labourers and low level of education. Oks also reports on the harsh punishment – corporal punishment, executions – meted out to those who rebelled. At the same time he called upon his readers to protect the rights of an individual and demand social-political innovations. 1905 played an important role also in the aesthetic development of the writer as the first album of the literary group Noor-Eesti (Young Estonia) appeared in summer. There was nothing by Oks in the first issue but the next ones certainly published him.

The writer as a person was quite controversial during his lifetime and has remained so even today. He and his work have often evoked contradictory opinions. He has been hailed as a genius or a sick degenerate man, etc. One of the leading figures of the Young Estonia movement, Friedebert Tuglas, said: His moods are often morbid, pathological, passionate-whining. Such emotions seem almost leprous, experienced too personally, and hence their verbal expression contains much that is different and what we usually regard as ‘literature’. Other opinions about Oks include that of the Finnish-Estonian writer Aino Kallas who wrote shortly after he died: The enfant terrible of Young Estonia in the direct sense of the word was the recently deceased writer Jaan Oks. /—/ His appearance was just as sickly as his art /—/ Jaan Oks was justified to call himself a decadent: he really was one, in body and spirit, in art and in life. /—/ He was a mixture of a genius and a nervous wreck.

Another Estonian literary figure, Artur Adson, wrote on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of Oks’s death: Oks would certainly be a suitable object for a psychiatrist with literary leanings.

A few dozen or so years later, in 1956, the psychiatrist Ivar Grünthal gave perhaps the best medical evaluation about Jaan Oks. He wrote: Proclaiming Oks insane constitutes an abscess on the corpse of Young Estonia, embalmed with expensive ointments. Pus has to be let out so that the fallen hero could be celebrated in eternity in the shape of a glittering scar. And elsewhere: The life and work of Oks does not reveal any significant signs of his bodily or mental abnormality. /—/ His last week of intense suffering, and his sensitive and spiritual art could have given reason for stuffing him hastily into the straightjacket. Such a myth has been fed by heedless minds and ignorance.

I would also like to refer to the article of another Oks scholar, Kalju Leht, who paid special attention on the writer’s childhood. Of the breakthrough point in Oks’s life, Leht writes: This part of his life definitely refutes the opinion of Oks as a recluse. I cannot find any aberrations in either psychic or ethical sense, if we don’t consider the independence of thinking, originality of behaviour and especially the rebuttal of everything conventional as some kind of deviations.”

One person who describes the mental condition of the writer was his brother Eduard: Jaan fell ill, i.e. mentally, after autumn 1910 in Samara when I took up my military service and he was left on his own, without any help. He was quite well before, truly healthy, although showed signs of some strain. He used to rush out of the classroom, hurl the book into a corner and run around in the room. Sometimes he upturned a plate of soup, or tore a paper or a magazine to shreds, muttering to himself about rubbish being printed.

We could try and approach Oks’s work and interpret it from psychoanalytic point of view. Daniel Palgi wrote about Oks’s style from a linguist’s viewpoint in 1927: The sexual note is obvious in the writer’s preference of some words, for example ‘naked’: ‘naked stones’, ‘worn-out bodies’ etc. Psychoanalysis can draw its own conclusions from these and many other words, the author’s sexual undertones are clear to the reader. Some branches of psychoanalysis (Lacan in France) deal with linguistics as well, trying to find hidden symbols in words and images. In the work of Oks no symbols were needed as the sexual message was clear enough.

Yet another Estonian writer to tackle Oks was Johannes Semper who wrote in 1927: His every sentence is an event. It emerges from the depths of the subconscious, ideas and associations are not joined by peripheral manner but emerge from the centre, the deepest bottom of the soul. /—/ The sentence of Oks is not keen on round dances with others like itself, it does not appear at the expense of its neighbour or thanks to it, but comes from below, regardless of whatever happens to be next to it. This kind of sentence is autonomous.”

These are not empty claims because Semper was the first who tried to apply the Freudian method of analysis in Estonian literary science. As for me, I would like to ‘squeeze’ Oks’s work into the framework of Freud’s conception, as the other psychoanalysts are time-wise excluded because Oks wrote his main works in 1906-1909. It must be admitted that it is most unlikely that Oks had read anything about psychoanalysis. He could have been influenced by Nietzsche and Schopenhauer, in a sense intellectual fathers of Freud.

One of the major Estonian writers, Friedebert Tuglas wrote about Oks: Together with poems Oks has produced several hundred works of literature. Most of them unfortunately ended up in waste paper baskets of editors who regarded themselves people with impeccable literary taste. What we now have of his work are modest odds and ends. Oks was perhaps the most typical of all those writers who belonged to the Young Estonia group and caused such a breakthrough in Estonian literature. His manner is most straightforward, sharp, purposeful, from the very first writings to latest fragments written on book covers in his deathbed. His role in our literary revolution is definitely considerable. /—/ Jaan Oks has taken our literary subjectivism further than any other. He produced prose and poetry and criticism. His Dark Child of Man could be the most moving and deepest prose work in Estonian literature. His main contribution can perhaps be summarised in the claim that he ennobled our naturalism, afforded it subjectively poetic tones, made it deep, to the very roots of life, lifted it to the status of myths, enriching it with sarcastic bathos and a peculiar vague romanticism. It was such a new and select art that it obviously failed to earn any recognition from our official reviews.

Adson wrote about The Obtuse Soul: I read the short story An Obtuse Soul. The places that seemed obtuse (but still captivating) before are now clear. The story has been written with an aching heart, with a proud defiance of a stubborn person /—/ Each sentence reveals the essential nature of a poet. He keeps talking in pictures. Wherever his pen goes, words spring to life. There is no need for illustrations. This is a true master of words. However, an artful word is only one half the weapon for a proper writer, the other half is the intensity and scope of his feelings, and this is something Oks possesses in abundance, as only few have done before, or possibly after.

© ELM no 22, spring 2006