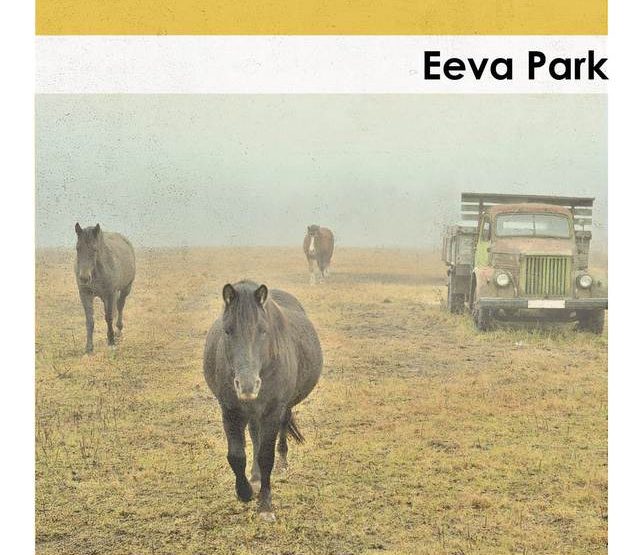

Eeva Park, Lemmikloomade paradiis (Pets’ Paradise)

Tallinn, Verb, 2016. 239 pp

ISBN: 9789949984138

Eeva Park (1950) is one of those rare authors who is equally talented as a poet, a short story writer, and a novelist. She has an infallible ability to recognize what kind of story, idea, or imagery to use in which particular genre. Park wrote the novel Pets’ Paradise (Lemmikloomade paradiis) in the autumn of 2016. At first glance, one might think it was meant primarily for other authors, reviewers, and literary enthusiasts: at the center of the plot is a young woman with lackluster literary interests who spends some time at a writers’ house in Ireland. Yet, as is common with Park’s writing, this picture is deceiving. Things are not necessarily what they seem, and the text’s broader nature gradually unfolds, peering deep into the human psyche.

Pets’ Paradise isn’t a romance novel, although this may be a layer that is immediately revealed to the reader. True, the protagonist is in a writers’ house, recalling in diary format her relationship with a complicated and dangerous, but nevertheless attractive man. Yet, it is not a work about a woman longing for a man.

Perhaps the novel’s third and most important layer is its story of finding, understanding, and making peace with oneself. The process may sound short and simple when stated like this, but Park manages to present even the simplest things in a varied, deep, and well-considered way. Who are we to ourselves? What is the affect we have on others? And, what is perhaps most complex: how can we ever understand who we truly are in the face of superficiality and the deception of ourselves and others? How can we ever be capable of understanding and coming to terms with ourselves?

The positing of such questions and the quest for answers matches ideally with the milieu of the writers’ house. What makes this even more intriguing is the kind of house described in the novel: a place governed by odd and very particular rules. The patron, an eccentric aristocratic woman, allows the writers who comprise the cast of characters to reside and write at her abbey-like Irish country manor, but only under the condition that they obey several rules that are stricter than usual: the occupants are forbidden from interacting with one another, from leaving the building, and from concentrating on anything other than their writing. What is there to do for a young woman who ends up there by chance: one who, in reality, lacks any literary ambitions or intentions?

By situating her heroine in these unusual circumstances, Park creates a unique opportunity to delve into the depths of the woman’s soul. Though, to be exact, she allows the character herself to do so. Namely, the protagonist starts to write. To herself. Or is she writing to the world? As the book wraps up, it remains unclear what ultimately becomes of the manuscript the character wrote in the hopes of finding herself. As the protagonist leaves the house, she erases everything on her computer; whether this also includes the pages she wrote, excerpts from which are presented to the reader, is never confirmed.

And rightly so, for Pets’ Paradise is a journey. It is a voyage into the main character’s soul, but at the same time also into the reader’s soul. The book’s language is truly poetic: one pleasantly noticeable aspect is the stylistic difference between the narrator’s voice and the protagonist’s own writing, which feels more agitated and rough, yet is very sincere and invokes sympathy. Still, the style can occasionally come off as startling in its bluntness and rawness. Readers will find nothing grotesque or profane, but Park doesn’t shy away from addressing even the most complicated of issues: domestic violence, crudeness and intrigue in human relationships, pain from the loss of a child, and humiliations that one can inflict upon another person. All that pain can be found in this work, and Park makes no attempt to sugar-coat the topics. Nor does she move in the other direction: she doesn’t find it necessary to use profanity or obscenities, because what would be the purpose when life itself is already so complex, often cruel, and filled with deceptive, unfulfilled hopes and dreams?

Nevertheless, this doesn’t mean Pets’ Paradise is a work of angst. Park manages to keep the positive and the negative, the sad and the happy in check. Both poles exist in life, and often, it is only a question of perspective. Even though the book may appear sorrowful at times, this is not the case. It may be painful, but the pain that Park describes is mostly cathartic. And as the author herself said at one book-signing event, even a love that has been lost and irrevocably fallen into the past is good and beautiful for one simple reason: because it existed. And that is undeniably worth something.

Peeter Helme (1978) is an Estonian writer and journalist, and anchors Estonian Public Broadcasting’s literary radio programs. Helme has published five novels. The latest, Deep in the West (Sügaval läänes, 2015), is a drama set in the industrial Ruhr Valley.