A woman furtively squeezes the rounded surfaces of hard, unripe pears in her purse: she must somehow change the mind of a man who is threatening to rape her. Stepping out of the bathtub, the protagonist feels such unexpected relief that her legs appear at odds with her weight and that her freshly-washed head is seemingly enveloped in emptiness: she is bathing for the first time after lying low in an abandoned house for weeks. The dense reek of a fart spreads across an entire bus, causing the riders to look up and wrinkle their noses: suddenly, the narrator is convinced that she is the one responsible for the inhuman stench, so she gathers up her bags and quickly makes an exit.

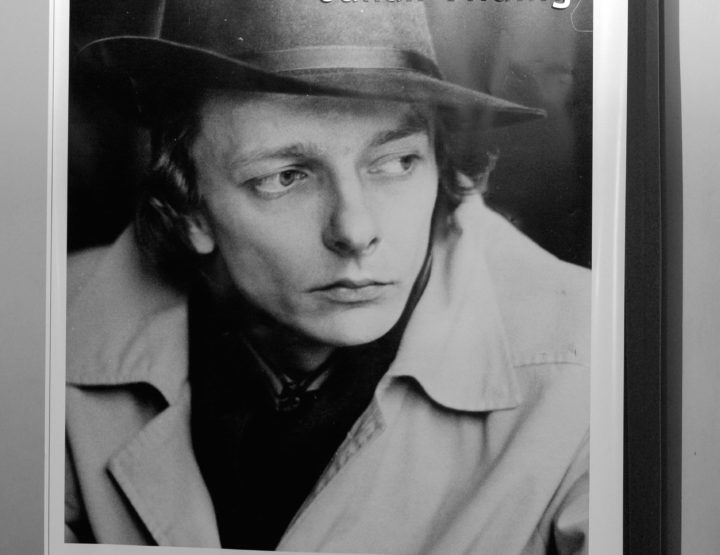

For me, Eeva Park (b. 1950) is above all an author of the senses: one who records keenly noticed sensations with convincing brevity. She has remarked that when writing she finds it important to stir the undercurrents of the reader’s memories, and it is as a result of these succinct but sensation-rich descriptions that her books are often so successful.

Maybe that is also why Park has only written infrequently for the theater: in drama, the sensations come from elsewhere and are already in abundance – the task of the text is different in playwriting. In other genres, however (in shorter and longer prose, as well as in poetry), by beginning with these sensations, the author is able to arrive at an impressive variety of places.

Park’s earlier prose can be classified as more traditional psychological realism, in which she blends and reinforces meaningful everyday moments and the flickering of the human psyche with bodily sensations. Her pair of family novels Dust and Wind (Tolm ja tuul, 1992) and A Student of Laughter (Naeru õpilane, 1998) are about the disintegration of a multi-child family, telling of its members’ relationships with one another mainly through the perspective of the daughter Mirjam. Most Estonian readers are well aware that Park’s subject matter is greatly taken from her own personal life. Her parents were renowned Estonian authors whose divorce is carved into local cultural history. As a result, Park’s family novels have also been consumed out of a greedy hunger for gossip. Yet, this fact doesn’t diminish the books’ artistic value or how sensitively their mundane scenes are described. Her earlier short stories also often convey little everyday instances, in which readers can vividly imagine the palms perspiring in an uncomfortable situation, the mind dazed from bright sunlight, and the cracked lips on a hot summer day.

Neither this dense sensual quality nor the realism it achieves diminish to any degree in Park’s later prose, although the works stand out more as thrillers with social stress or social critiques with thriller stress, whichever way you take it. Her best-known work is probably the novel A Trap in Infinity (Lõks lõpmatuses, 2003; winner of the 2004 Eduard Vilde Award), from which the bathtub scene at the beginning of this article was taken. The book is about an Estonian girl whose boyfriend traffics her to Germany for prostitution: a plot somewhat similar to the acclaimed Lukas Moodysson film Lilya 4-ever (2002), which was released at about the same time and was also partly filmed in Estonia. Yet, significant differences between the two (at least for the Estonian audience) are the facts that Moodysson showed Eastern European exoticism through an external gaze, and the main character of the film is a member of the local Russian minority. Park, on the other hand, wrote about an ordinary Estonian girl, and in doing so emphasized that this is not merely an issue prevalent on society’s periphery.

Park’s approach to writing thrillers is to reveal a large part of the facts only as the story progresses: something criminal is afoot, and tension is ratcheted up until it reaches a climax. A thick, psychologically-charged membrane grows over a dramatic and venturesome skeleton, predominantly by way of the author’s sensory descriptions. The first sentence in this article, with its unripe pears, was taken from Park’s short story “Chance Encounter” (winner of the 1994 Tuglas Award for Short Stories): the reader waits with bated breath to find out if a woman hurrying home to her child will arrive safely or be raped and killed by a truck driver. In addition to Saul Bellow and Sherwood Anderson, Park has named authors of American detective novels as her international literary influences. Her psychological thrillers perhaps share an element of Scandinavian noir, although it wasn’t yet a phenomenon at the time she wrote them. Park’s A Trap in Infinity has been translated into Norwegian and Swedish, as well as into German. Park’s works sometimes tend to slip into the crack between “literary fiction” and “thriller”: a crack that many literary scholars certainly try to itch, but which nevertheless endures, at least in many readers’ subconscious. On the other hand, her more widely-read works were still included on school reading lists even when contemporary literature was merely skimmed over in mandatory curricula.

The dimension of social criticism is also prominent in Park’s short-story collection An Absolute Master (Absoluutne meister, 2006), which ventures into the murky world of fishing in freshly independent 1990s Estonia. It includes, for example, the short story “Vilnius Alibi”, in which a shadow of intrigue is cast over the 1994 Estonia ferry disaster at a time when the young state’s anarchic economic situation was dominated by fake names and shell companies. The collection’s title story tells of a woman who becomes impoverished after being returned ownership of her grandmother’s house, which the Soviet regime had seized (the story is the source of the bus scene at the beginning of this article). Park cynically depicts fraudulent real-estate agents and construction companies, as well as the protagonist’s daughters, who dream only of moving abroad and completely disregard their mother’s dream of a cozy life. The youngest daughter’s snide accusation gives the collection its title: “Honestly, Mom, you’re an absolute master of getting yourself into all kinds of problems.”

A character’s close but tense relationship with her mother is a motif that permeates Park’s works. Whereas “An Absolute Master” reveals the mother’s point of view, we more often encounter a mother who, seen through her daughter’s eyes, is neurotic, usually unfair and self-centered, but still loving and caring in her own way. This may be regarded as a typical “women’s literature topic” and, to be fair, Park’s social critiques predominantly lie in the sphere of women’s rights: trafficking and the forcing of girls and young women into prostitution, threats of sexual violence, and asymmetrical relationships in terms of age and status. Critics have frequently remarked on the strength displayed by Park’s female characters. For example, unlike the protagonist of the film Lilya 4-ever, the main character of A Trap in Infinity finds strength in deciding to take revenge upon her trafficker. Yet one still must recognize that Park is, in a sense, a pre-feminist writer. She is kindred to the Soviet and post-Soviet female Russian writers who have strongly rejected calling themselves feminists. Even in slightly more everyday situations, she tends not to thematize male–female relationships from an equal rights standpoint: she isn’t concerned with the sharing of domestic chores and doesn’t perceive women as being systematically subjugated. Rather, she characterizes relations between the genders as a force majeure.

Park is indeed a romantic author by nature, which is demonstrated by how resolutely she refuses to tear away the veil of romance completely, even when describing a (psychologically) violent relationship, and by how she does not empty the cup of glittering enchantment. Her latest novel, Pet Paradise (Lemmikloomade paradiis, 2016), describes a young woman’s escape from an exhausting, addictive relationship. It’s clear that a temperamental and alluring man has behaved very poorly with the protagonist, but she refuses to adopt the role of victim and can’t bring herself to cease cherishing memories of passionate moments, exotic trips, and “the good times”. It’s no secret that addictive relationships often tend to go this route, but in Park’s case the cause appears to lie primarily in a basic manner of understanding love. The author has jokingly confessed her own fear that the novel might be too romantic, with which her colleagues disagree. Whether Park’s female characters happen to be trustworthy, complex, and multi-layered in spite of her romantic tendencies or precisely because of them is probably a question of worldview. In any case, this stands out noticeably on the Estonian literary scene, where authors’ voices commonly prefer to maintain a safe, thoroughly considered, and even smirking distance from the subjects they address.

Park, on the other hand, cracks relatively few jokes, and when she does, it is in a concise poetic form. It appears the immense weight resting upon every word compels her to, if not engage in wordplay outright, at least equip the writing with linguistic twists. The poetry samples selected for this edition of Estonian Literary Magazine demonstrate this facet. By exercising the nuances of language Park deals not only with the world, but also with linguistic perception. Nevertheless, even her poems are often prompted by the sensual description of a fleeting scene or an earlier episode that reminds the lyrical ego of a certain sensation. Thus, the feeling and the idea are juxtaposed basically in the same way as in Park’s thrillers. Once again, it is clear that Park can talk about big topics through little things.

Johanna Ross (1985) is an editor of the Estonian philology journal Keel ja Kirjandus (Language and Literature). As a scholar, her main fields of interest include

female and Soviet literature.