When did you start writing poetry? What was the feeling when you started writing poetry?

I wrote my first poem when I was probably around 16 years old, though at the time I had read very good poems quite enthusiastically and I thus threw my own texts without any hesitation – this went for both poetry and short prose – into the fire. But I remember that I left my extremely romantic adventure novel written when I was between 12-14 years old at the bottom of my wardrobe, my secret place. I never thought of showing it to anyone. Later this quite bulky “manuscript” disappeared from the wardrobe God knows where.

I started writing again 15 years later, when one night I woke up, hurried to the kitchen and wrote a poem on the corner of a paper that I happened to find. I was physically exhausted at the time, the children were small, I was carrying bricks at the construction site of our house, digging the garden – so in other words I didn’t start writing because of an excess of time or strength. The poem about Nimrod’s winged bulls was finished while digging up the potatoes in an autumn rain, and all of those things together – a bucket full of potatoes and the poem – made me free and happy like never before.

I know that you are the organizer of the Nordic Poetry Festival. How long have you been organizing that? How did you get involved in the festival? Are there any special moments you can remember from that?

Eha Vain, the main organizer, invited me to work for the poetry festival and that moment was very memorable, because we didn’t conduct any negotiations at all. Eha asked on the corner of Harju street if I would agree to do it, I answered yes, and these short questions and one-word answer have now grown into collaboration that has lasted six years.

I was a part of the organizing of the Nordic Poetry Festival since 2001 and for me the first one of those was special, because I had to come to terms with the organizational matters, which before that I had no idea of at all. I have to admit that the most exciting experience in working with the poetry festival was the people of the Tallinn office of the Nordic Council, our work group that became a real community, with Jan Kaus who was always offering new ideas and Külli Ummer representing the National Library. Estonian literary life is rather lacking in communication, and contacts with colleagues are almost non-existent and one important part of a poetry festival for me is that I have got to know not only Scandinavian, Latvian, Lithuanian and St Petersburg poetry and poets, but also Estonian authors, including young authors, whom I otherwise would not know that well.

The most memorable for me were Faroese Torododdur Poulsen’s and Latvian Dace Sparane’s visit to a secondary school in Tallinn, where in a literary gathering they presented translated texts, chosen by the children beforehand, in the original language. The contact, which came out of that thanks to their poems, was so powerful that even after the school bell had rung the pupils didn’t leave us, but continued reading poems.

Are there certain themes that you feel run throughout your poetry? Are there any poets that you would call influential in your work?

Someone once wrote about me that I was trying to discern real and imaginary values…

I don’t know, I don’t know how to explain why my poem are born and I feel that if I was able to fixate it precisely I wouldn’t need to write poetry anymore.

From the poets the first that come to mind are Lorca, then perhaps Tagore, Alliksaar, Liiv, Under, Manner, Turkka, and Yeats. But also Japanese haiku in Thomas Anhava’s extremely good Finnish translation. It’s hard to name and leave others unnamed, the list is still long. Authors whom my mother Minni Nurme translated, are also important for me: Byron, Shelley, Heine, and Frost.

You also translate Finnish poetry into Estonian. How did that start?

I once translated with a true beginner’s boldness Eeva-Liisa Manner’s play Eros and Psyche for the Drama Theatre. Later I first and foremost translated Finnish authors who participated in the poetry festival, though at the poetry festival I have tackled texts by Latvian and Russian and other authors. This kind of cooperation is highly meaningful, because often the question lies in an unexpected angle of approach. Working with texts has always been interesting, even when the poem being translated isn’t so exceptional. Who is going to be the favourite of the poetry festival public, is not easy to guess in advance, because there are poets whose personalities and performance give the text resonance, which isn’t so powerful while just reading their work.

As a translator, are there special rules you try to follow?

The main rule is that in translating a poem I must have time. A text that has already been translated needs to be left alone for awhile, so some time can pass and you can look at it again with fresh eyes, as almost always new possibilities and better solutions emerge. A translation is never really finished, it can only become closer to the original.

Are there sources for your inspiration that you go back to again and again, for example, a place?

At one time the village of Kiini in Viljandi country, my mother’s home, was that place. I spent all of my summers there, but now Estonia in general is my main source, because I feel and perceive this spot here more and more.

I have read that the word poetry was the most popular search word in the Estonian server www.neti.ee. Do you think that Estonians are a nation, where poetry plays an important roll?

I don’t believe that Estonians as a nation are very different from others. I have a feeling that percentage-wise we conform in both good and bad terms to the average European level. There is also a myth, that we are a big singing nation. We do have our choir singing, our singing festivals, but singing at family get-togethers just for fun really doesn’t exist anymore. But perhaps that is changing – in Tartu the singing of runo songs together is being practiced.

Do you think Estonian poetry is experiencing new trends?

It seems to me that a ‘new trend’ is when people know their own poetry first of all and then that of their circle of close friends, and perhaps it’s the reason why sometimes the laudatory tone they use to describe one another’s work seems a bit ridiculous.

Is there anyone in Estonian poetry that hasn’t been recognized by Estonian readers, but is worth reading?

There are poets in Estonia that are quiet – for example Mari Vallisoo, whose new poems can’t be read, because she doesn’t write any, though I am looking forward to them. Triin Soomets and Doris Kareva in my opinion are true poets.

I consider Indrek Koff the best young author of last year, whose first poetry collection clearly distinguished from the general bulk of poetry. But it’s always so that some poet, who has left you feeling rather indifferent, can unexpectedly move you powerfully with his or her texts. This is why I think you shouldn’t leave anyone out, but seek out and read also those whose names aren’t lit up like a neon sign in official literary heaven.

© ELM no 25, autumn 2007

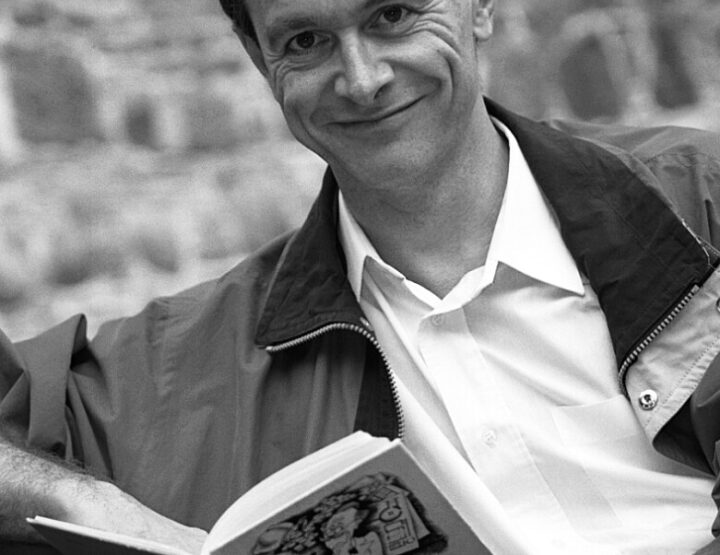

Interview with Eeva Park

By Jayde Will

Eeva Park –

Share: