Madis Kõiv: Near Kähri Church at Pekri (Kähri kerko man Pekril)

“Studia Memoria” II. Võru: Võru Instituut, 1999. 232 pp

Estonian literature of recent years has been deeply concerned with postmodernism and the widespread use of international subject matter. Contrary trends, however, are prevalent in the works of stronger regional colouring. Poetry, and longer works of prose have been published in different dialects. This trend is the most remarkable in South-Estonia, or among the authors who have come from this region. The Võru dialect has been used earlier, on occasion, as a language of poetry or a poetic tool. Ideologists of the Võru dialect are trying to help it to achieve the status of a literary language. They have worked out the orthography, published a primer, textbooks, calendars and even some metatexts.

One of the most important developers and enthusiasts of literature in the Võru dialect, besides the poetess and prosaist Kauksi Ülle, is the physicist, philosopher and playwright Madis Kõiv. His biggest prose work so far is “Studia memoria”, which consists of four rather loosely connected volumes, each bearing its own title. This year, the second volume of Kõiv’s series: Kähri kerko man Pekril, which had been missing so far, was published. This is a saga-like novel that follows the development of the author’s family lineage from the 19th century up to the 1930s.

Kõiv uses parish registers, letters, postcards, and photos to reconstruct his more recent family lineage and in the absence of written sources, legends to reconstruct the earlier times.

He documents the circumstances of lost times precisely, trying to describe his own one-time sensations of colours and smells. The book is divided into two parts by a postcard that was sent home from Marseilles on which the astonishing question: “Is Madis still living?” was written; Madis was no more than a year old at that time. The sender was Kõiv’s mother, who had abandoned her son. The remainder of the novel is comprised of previous consultations and explanations concerning the past, answers to endless questions, the small boy’s first sensations of the surrounding world, perceptions, and memories. The mother’s question stands in front of the writer in all its existential hardness.

The distinctive feature of Kõiv’s prose is not as much the reconstruction of the past in the form of sensations as the attempt to describe the process of remembering. Thus, we have a study of memory. Unlike Kõiv’s other works, the narrator of this book is not a scholar, but a farmer imitating a philosophical way of speaking. He is reminiscent of the farmer who occasionally ambles across the stage in Kõiv’s play “Meeting”, about the meeting of Leibniz and Spinoza. The virtue of this book is in the harmony of the language and the speakers’ perception of the world.

Hannes Varblane: Openly Bad: A Selection. (Avalikult halb. Valik)

Tartu: Ilmamaa, 1999. 96 pp

Hannes Varblane’s first book, a collection of poetry entitled Mäel, mis mureneb (On a Mountain that Crumbles), was published in 1990. It was awarded the Betti Alver Literary Prize for the best debut of the year. Four more collections of poetry have since been published. The latest of them, Letaalse lõpuni (To the Lethal End) was released only last winter. In Avalikult halb selections from all four books are presented together; it was published for the 50th birthday of the poet.

Varblane is not as much a modernist or a postmodernist as a poet in the classical sense. The 1960s and its idols fascinate him. His models, however, belong to another time and genre— music rather than literature; Jim Morrison and The Doors, 10 Years After and the blues of that time have influenced the development of his poetry. Traces of the beat generation and the movement of hippies are also apparent in his work.

Varblane’s poetry is mostly in free verse. It is expressive and pointedly subjective. His poems often seem like fragments torn from a world-weary scream, boldly accusing god, the petty bourgeoisie, or the rulers and oligarchy of this world. Varblane’s greatest virtue is his honesty, which lacks any poetic mimicry. He tears pieces from his inner world with love or hate and tosses these pieces, his poems, to the reader.

For Varblane, writing poetry is a way of living. He writes anywhere, in great amounts and with a Henry Miller-like passion. He writes on anything that might come in handy including paper bags, napkins, cigarette packages or newspaper edges.

When faced with making selections for a book, Varblane is extremely critical and particular. The poetry in Avalikult halb, compiled by Urmas Tõnisson, was evaluated twice to ensure that the final publication really does contain the author’s best work.

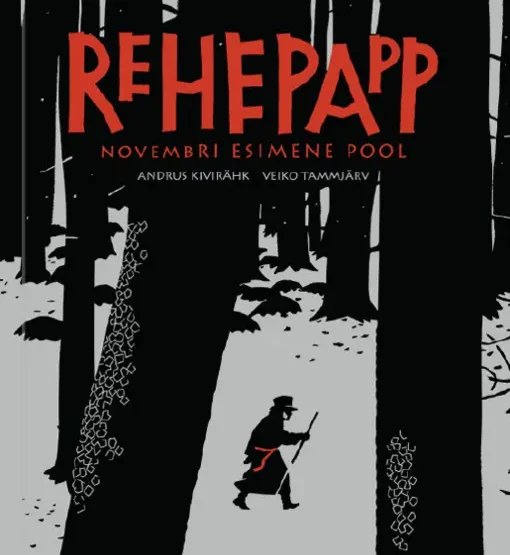

Andrus Kivirähk: The Butterfly (Liblikas)

Tallinn: “Tuum”; 1999. 149 pp

Andrus Kivirähk made his debut in 1996 with Ivan Orava mälestused (The Memoirs of Ivan Orav), a book of fictive memoirs. It examines more than fifty years of Estonian history through the eyes of a person close to the powers. Kivirähk conveys these “memoirs” with extremely sharp grotesque and humour. Ivan Orava mälestused evoked contradictory impressions. More conservative readers felt that Kivirähk had turned history upside down; his depiction of Estonian independence before WW II with comical and caricature exaggerations was sacrilegious. The critics, on the other hand, deemed the novel remarkable for its lively fantasy and the author’s good penmanship. They appreciated his skill in saying a laughing good-bye to the tragic past.

The characters in the novel Liblikas are also derived from history. This time, Kivirähk has skilfully merged his flying fantasy and man’s inherent sadness over lost, beautiful times. Belles-lettres are manifested as fiction, artistic lie, through his narrative skill and enjoyment of these skills.

Liblikas is about theatrical life in Estonia in the first decades of this century and the birth of the national theatre “Estonia”. It centres on the young actress and dancer Erika Tetzky, whose meteoric flight in the sky of theatre was pressed into everybody’s memory by her early death. Tetzky was a young, fragile, butterfly-like creature. Her nature and the two-winged building of the theatre, completed just before the WW I, inspired the title. The fate of both of these “butterflies” merges into one, when an ill-boding, grey dog is seen at the construction of the theatre or near Tetzky; this dog is an omen of death. During the war, the theatre building fills with the wounded and dying. Consumption takes 24-year old Erika Tetzky to her grave. Tetzky’s dead husband as narrator is integral to the novel’s poetics; he survived her and later died. He recalls in nostalgic colours his earthly life in the theatre and how he found his beloved wife.

There are certainly more legends and myths in Kivirähk’s novel than truth. Knowledge of history is, therefore, not necessary to understand Liblikas. A few episodes, names and dates from cultural history provide the framework or scenery for the novel; the author has filled them with binding substance, rich in allusions ranging from folklore to world literature motifs. What could better suit discussions about life, theatre and their relationships than a romantic myth about a dazzling dancer who died young! The novel, however, is not tragic and does not philosophise about art. It is a successful mixture of comedy and sentiment, exaggerated anecdotes about theatre and the mystical-magical world view of popular stories.

Kivirähk’s novel glorifies art and theatre, which help to overcome death and rise above the vulgarities of every-day life.

Juhan Paju: Grandmother’s Manor (Vanaema mõis)

Tallinn: Varrak, 1999. 255 pp

Juhan Paju (1939) is another much published author of the 1990s. His novel Vanaema mõis placed fourth at the literary competition for novel writing in 1998. This book was a prize contender in previous years, however, with many other notable works entered, the competition was very close.

Juhan Paju is a fluent story writer; the language and old-fashioned style of his books make them popular. The inner life of his characters are given only in outlines. His strengths are his skillful, imaginative plotting and his choice of subjects, which interest local readers.

Vanaema mõis discusses a subject dear to the hearts of the older generation – the events in an Estonian village during the complicated years of the 1940s. The book is set in 1941 in a village that is still full of the idyll of older times. Two beauties compete for the love of the musician Mati, the village’s lady-killer. One of them is the beautiful daughter of a farmer, the other is the seductive daughter of the village militia officer. The unforeseen events that follow give the readers, tired of tragic stories about the same historical events, a new, lighter outlook.

The unanticipated deportation and the outbreak of the war forcibly interrupts the serenity of the village people’s traditional way of life. Some are deported to Siberia or taken to labour camps; others manage to reach the free world after a perilous sea journey. Exile Estonian writers, and later writers in Estonia, have often written about these events. They stress the historical injustice and the oppressiveness of the era. Paju depicts the same events, hinting that he knows the fate of his characters. He doesn’t tell a tragic story, but an everyday, historical adventure. Even though it is full of tension and excitement, the reader can hope for a happy end. The life of Mati, the central character who is deported to Siberia, adds spice to the book. He becomes a soldier in the Soviet Army, and later in the German Army. In Siberia, he has two wives and four children. In Estonia, he has a third wife, whom he seems to love the most, and two children. After the war he hides in his home village, but fate is always taking him away from his beloved wife; he has to go back to Siberia to hide himself from the Soviet powers in the end. The grandmother’s manor, the title of this novel, is only mentioned in one episode when the characters dream about reconstructing it. This gives the reader the impression that the author intends to write a sequel to this book in which those people who fled to other countries will return to make their dream come true and reconstruct the manor again.

Henn Mikelsaar: Criss-Cross on a Treadmill (Ristiratast)

Tartu: “Ilmamaa”, 1999. 133 pp

Henn Mikelsaar (1943) has won two literary novel-writing competitions. His novel, the winner of the First Prize in 1998, has received only favourable reviews from critics.

In Ristiratast, a kind of dislocated world of the novel contrasts a comfortable, but disappearing environment to a new, forthcoming one; in particular, an old, winding road is set in contrast to a new, straight highway called VIA. Mikelsaar enjoys writing about opinionated eccentrics; those in this instance, are content to remain oblivious of a road roller from the beautiful, new world which could roll over them. There are two main characters: Aalon is the man who cleans roadsides, and his friend Tehvan is a stonecutter. Aalon loves the old road with all his heart and works to keep it clean and in good order. He hopes that his efforts will not go unnoticed and that he will still be needed for a long time. The old road appears to him as a beautiful cemetery alley, bordered with cenotaphs erected for those who have lost their lives in road accidents. All of the stones that mark the places of accidents have been made by Tehvan. Like Aalon, who wants to serve beauty, Tehvan wants to serve the spirit. He is waiting for inspiration to write a real holy writ, which is the Newest and devoted to the Spirit, like the Old is devoted to the Father and the New to the Son.

Aalon and Tehvan, both selfless and undemanding men, still dream about being needed and admired in the new forthcoming world; this world will centre around the new road VIA. Naturally, the new will sweep aside the old, directly and indirectly. The church will be taken apart and erected again in a new place. The river water will wash away the soil. VIA and the river run crosswise across the parish of Jooru, which after the completion of VIA is waterless and parched like a desert. Aalon, like a squirrel which had run criss-cross on a treadmill, is left without work. Nobody needs this true spirit any more who had ungrudgingly cleaned up all rubbish left by his fellow men and sentimentally registered the trademarks of mass culture and trivial truths written on the cenotaphs.

The success of the novel lies not in its lapidary plot summary, but in the hidden way that it is presented, and in its special magic world, which avoids the moralising warnings that anti-utopias usually give.

Asta Põldmäe. A Girl of Vienna (Viini plika)

Tartu: “Ilmamaa”, 1999. 180 pp

Asta Põldmäe is one of those writers, who works words into filigree and who can make even the most banal situations fresh and unexpected.

The title story, A Girl of Vienna, rises above the other short stories of this collection, and has a significant place in Estonian prose as well. The girl from Vienna is the youngest daughter of the first, great Estonian poetess Lydia Koidula (1843-1886). The girl was born in Vienna, grew up in foreign countries and never knew a word of Estonian. There is one photo of her taken sometime in the 1930s; she is standing in front of her mother’s statue in Pärnu.

The Lydia Koidula of Põldmäe’s short story, which could actually be called a short novel, is a heavily pregnant woman who walks the icy streets of Vienna in a dense snowstorm in January of 1878. She is dragging a sledge behind her with one hand, and leading her small son with the other hand. The author stresses the eternal antagonism between creativity and reproduction from a woman’s viewpoint. Moreover, she examines everyday life through the all-knowing future. The romantic tradition has much emphasised Koidula’s conflict between the everyday life of a wife and mother, and the role of the poetess as a national-romantic heroine. The story of Koidula’s family, and the gradual perishing of the poet inside her as she yielded to marriage and everyday life was performed in an extremely romantic key in Estonian theatre during the 1930s. A later, documentary play based on the correspondence between Koidula and Fr. R. Kreutzwald has been repeatedly performed.

So far, the prose genre has been quite helpless in deconstructing this national myth. Põldmäe wipes centuries of dust off Koidula’s story. She does not stress the tragedy of the poetess commenting: “It was known that after the birth of her third child, the girl of Vienna, Koidula will quietly and without rebellion sink into ‘the prose and real life’.” Only the extremely wise fate – a quote from one of Koidula’s letters – knows the long-term meaning of everything that takes place. Põldmäe’s view of Koidula’s “real life” is suggestive and intriguing.

The collection contains seven other psychologically interesting short stories in addition to the longer title story. The author’s skill can be noticed already in the first short story entitled Sula (Thaw). She gives the banal plot of a wife coming home to find her husband with another woman a new twist when she introduces a fourth player – a man who collects peoples’ answers for a demographic survey. In her short stories, Põldmäe very often brings together totally different worlds, and different people, who cannot reach each other. The hidden tensions often find tragic solutions. As an author, she often looks at her characters from a god-like position, as a psychoanalyst and a commentator; her comparisons and point of view can sometimes be quite contrary to expectation. Põldmäe has also translated Spanish literature into Estonian. The emphasis on the presence of death in her work could indicate that she has adopted a Spanish attitude towards life and death.

Ellen Niit. The Song of Limestone (Paekivi laul)

Tallinn: “Virgela”, 199 . 364 pp

Ellen Niit (1928) has been a very important author for several generations of Estonian readers. She published her first poems as a schoolgirl, but she could publish her first book of poetry only during “the thaw” of the Hruschtschov time; accusations of formalism, which continued thereafter, hindered her. That collection, Maa on täis leidmist (The Earth is Full of Things to Be Found, 1960), has now become, together with Ellen Niit’s husband Jaan Kross’s first collections of poetry and the work of Ain Kaalep, the classical works of Estonian innovative poetry. Many poems from this collection have been included in school textbooks and have been made into songs which everybody knows.

The representative selection Paekivi laul, published to mark Niit’s 70th birthday, contains the author’s first collection, the two following collections (1970 and 1977) and later poems. Some of these poems have been previously published in her children’s books. Her poetry, prose and plays written for children have made Ellen Niit one of the most loved Estonian children’s author; she was considered “their own” writer for many generations.

Niit’s poetry, which differed much from the false optimism of the canon of the Stalinist era, and which was scolded a lot, especially for its free verse, is actually, written in a very clear and pure language; it is very optimistic, natural and fresh, full of the joy of discovering the world and the poetics of simple things. Niit glorifies feelings about home, everyday joys, the strength of basic values of life, family, and nature. She tells about the necessary belief in the sun, and in human goodness. She says that happiness is in one’s own hands; it grows out from the work of one’s hands. Her love poems are refreshing; the feminine viewpoint of her work values home and children, harmony and the perfection of wholeness, which can be found in every living being. In her later poems, we can also find the motifs of lasting and endurance. Thanks to the music of her language and simple, archetypal images, Niit’s poetry is well understood and much loved especially by children and young readers.

Toomas Raudam. A Living Suicide (Elus enesetapja)

Tallinn: “Virgela, 1998. 280 pp

Toomas Raudam (1947) has, since his debut twenty years ago, written one and the same text over and over trying to refine it to perfection and completeness. Besides this work, he has published a number of essays about the authors he considers influential, among whom Lewis Carroll and Marcel Proust occupy a special position.

The story Raudam writes, to make it even more complete, more full of different pictures, is the coming-of-age story of a young man, given in different versions. Among his characters, a son (sometimes a daughter) and his or her parents occupy the central positions; now and then other members of the family are added as well. The scene is laid in the atmosphere of a small town in the 1950s. He has tried to render his story in the form of a longer prose narrative (“Miks mitte kirjutada memuaare, kui oled veel noor”, 1990) and also in short stories. His story makes an entity out of a detailed description of the atmosphere, the inner voice of the main character, and the accompanying voice of an observer. On occasion, the author departs from his main subject and experiments with a parody and a self-parody (“Tarzani seiklused Tallinnas”, 1991). Raudam’s narrative moves on slowly, all the time examining the surrounding context, trying to peel it off layer by layer; his type of narration cannot be separated from language. For variety, he enjoys playing with language and the absurd.

The critics, including H.Krull, have called Elus enesetapja the best example of his style. In this book, Raudam explains his method: “The author sits at the table. He is worried. For a long time he has been tormented by a dream, which he knows will never come true, but every time he sits down to work, the dream returns to tease him again. He wants to be free and write such a book that would be free of any external dictation. This book – the author thinks it should be a novel – would include all that is surrounding him at the time of writing.”

Elus enesetapja contains four prose texts and a play, all of which could be called development stories. “Prado”, a story about a Peruvian exile, where the author’s voice commentates on the story or even interferes with the plot, moves on with a somewhat quicker pace than the others. The last story in the book is about a mother, who is dying of cancer, and her relationship with her son. It provokes a deeply humane succession of images that follow the story backwards from the epilogue to its true beginning.

Andrus Kivirähk: Baker’s Gingerbread Cake (Pagari piparkook)

Tallinn: “Kupar”, 1999 198 pp

Andrus Kivirähk wrote himself into fame five years ago, when he published Memoirs of Ivan Orav (Ivan Orava mälestused). Ivan Orav is a blacksmith, who was a youth during the time of President Päts and the pre-war Estonian Republic. He tells fantastic stories both from those beautiful times and of the terrorising deeds of the communists. In general, his stories are characterised by a lack of taboos, piled-up clichés and prejudices; word-plays and tumbling grotesques are also distinctive of his style.

In the 19 grotesque short stories from the collection The Baker’s Gingerbread surreal situations, plays of fantasy and the absurd are mixed. The story A Night Duty (Öövalves) is about a woman called Malle who works at a hospital. When she works the night duty she sees wondrous things in the mouths of the sick. There are scenes from the lives of dwarves in the mouth of one woman, a historical city in ruins can be seen in the mouth of another one, and in the mouth of a professor, Christopher Columbus’s ship “Santa Maria” sets out to a voyage. In the story A Brave Woman(Vahva naine), Marge becomes pregnant with a disc jockey’s baby and raises it herself while attending university. She knits sweaters at the lectures to earn her living and builds a house at night. Her perseverance brings her success; she later has some more babies, graduates from university, writes books and founds a bank. In the end, Marge takes revenge on the disc jockey. When her daughter has grown up, a young man comes to her telling that he has come to steal a big bell (a motif from a fairy-tale). They get on the back of an eagle and make their escape. All the motifs of a popular fairy-tale follow one after another; her mother pursues them, they drop a feather, and so on. Fairy-tales and beliefs, clichés and prejudices are mixed up successively. Unexpected turns in A Brave Woman reveal the absurdity of common sense. In The Story of My Love (Minu armastuse lugu), a young man marries a very beautiful girl, Maria. The twist is that instead of Maria, he actually married her father. The story unfolds as a quest; the young man has to pass three tests and finally finds himself content with the sadomasochist relationship with his wife, Maria’s father. This is a postmodernist playground, where everything possible gets turned completely upside down; ready-made pieces from soap operas, horror stories, fairy-tales, even song lines are all put together confusingly. The author’s fantasy is inexhaustibly composing new constructions. Sometimes, however, he does not make these images complete and he forgets to add some colour to them. Kivirähk has so many ideas that all his synopses could sufficiently provide for a whole team of writers besides himself.

Oskar Kruus. Hella Wuolijoki

Tallinn: “Virgela”, 199 , 303 pp

As indicated by the title, this book is about the Estonian-Finnish writer Hella Wuolijoki (1886-1954), a contradictory person with a powerful, creative personality. She was born in Estonia, but entered university in Helsinki. She also married and settled down in Finland. Sometimes successful, sometimes not, she always wanted to play for high stakes. Wuolijoki, a firm socialist, ran big businesses and was active in politics. She was familiar with many top politicians of Russia and the Nordic countries. She tried to influence the fate of Finland and spent the years 1943-1944 in prison for high treason. After WW II, she became the main director of Finnish state broadcasting. Wuolijoki began her writing career while she was still quite young, but her works in Estonian attracted less attention than the author herself. In the 1930s, she made a breakthrough with her plays in Finnish, which were very successfully staged in Northern Europe. Her internationally best known work was the play “Härra Punttila ja tema sulane Matti” (Mr. Punttila and His Farm-Hand Matti), which she wrote with Bertold Brecht. Unfortunately, Brecht usually didn’t mention her as a co-author.

Oskar Kruus regards Hella Wuolijoki as the most famous Estonian woman. This could be an attempt to promote her work, which has partially been forgotten; some of her plays have, in later times, been staged only in second-rate theatres. Although Kruus may have overstated her importance, her powerful, dramatic family sagas will likely remain among the core works of dramatics. Even her personal life could be considered a work of art. A number of books has been written about her life in Finland. In Estonia, this monograph by Kruus is the first one; he writes about her life with deep sympathy. Kruus, who has published a total of 23 books in several genres, has spent more than 30 years gathering materials about Hella Wuolijoki. His analysis of Wuolijoki’s work could be called relatively old-fashioned, however the discussion of her reception is full of facts and much space is devoted to the stage history of her plays. As the tradition of writing monographs about people died out during the Soviet period, Kruus’s book is very welcome. It gives a trustworthy overview of the conditions in Estonia and Finland in the first half of this century as reflected through the colourful biography of a woman author.

Hasso Krull. Jazz. Forty Poems (Jazz. Nelikümmend luuletust)

Tallinn: “Vagabund”, 1998. 54 pp

Hasso Krull, who began his writing career in 1986 under the pseudonym Max Harnoon, has published a number of poetry collections during the last dozen years. His development can be expressed as a movement from decadence toward poststructural models, but he also floats in a meditative mode. Krull’s poems seem to be generated mostly from secondary impressions; there are plenty of quotations, and often he either intentionally tries to lose his subject altogether or his texts hint at some other methods, derived from literary theory. The improvisations in the collection of poems Scales (Kaalud) were triggered by artistic photos, which were also included in the book.

Jazz, which consists of two cycles written with an interval of 4-5 years, is entirely devoted to jazz music. The book can be treated as a collection of recorded music, a set of two CDs, compiled by one person. Even the square design of the title on the cover of the book confirms its likeness to a record. Each poem in the book has been given its title after some famous musician of Charlie Parker’s generation. Some exceptions have, however, slipped in, such as Jimi Hendrix or Ice Cube. The poems are free verse and sometimes quite short-spoken. They presumably document free associations that have emerged when listening to the music. One poem imitates the magical frenzy of Jimi Hendrix, and another embraces an image which stemmed from Duke Ellington’s music— “I am living bread, coming from the Earth”. These are the best and the most striking poems in the collection. Such poetry, inspired by music, is just trying to catch the passing, fading sounds and fix them in writing.

The critics, who have thought about Ferlinghetti’s Jazz poetry as a standard for its kind, have remarked that Krull’s poetry is too full of Nordic coolness and that his images are too abstract. According to the author’s preface, the texts in the book can be connected to the music mostly by the freedom of improvisation. Krull himself calls the cycles in his book historical fantasies and explorations into the black music of big cities.

Mart Kivastik. Sparrow (Varblane)

Tallinn: “Varrak”, 1999. 159 pp

Family and growing up are recurrent themes in Mart Kivastik’s two previous books, a number of screen plays and a couple of plays that have been staged in Estonian theatres; these themes have been depicted in a slightly nostalgic retrospective and with rather sad humour. Sometimes he uses stronger language to add spice to his usually realistic way of writing. Kivastik has been praised for his dynamic style, laconic dialogues and knowing how to create atmosphere in his works. Reading Kivastik brings to mind the good old notion of humanism; his characters use low language and vulgarisms, are full of complexes and engaged mostly in everyday quarrels. It is paradoxical that despite these flaws, the world Kivastik has created always turns out to be habitable and worth living.

Sparrow, which based on its number of pages could almost be called a novel, was initially inspired by the Tartu poet Hannes Varblane. Still, it is by no means a key novel. Some biographical details and characteristic features of the prototype have been developed into humorous exaggeration. The scene is laid in a grotesque environment, which the reader, nevertheless, feels is absolutely real.

The character Varblane is a short-sighted and affectionate poet, who cannot cope with society very well. If he could, he would only to drink beer and write poems. Instead, he has to clean streets to earn his living and live on a dump. A tornado devastated the town, giving him much work to do. The storm also brings Anette, an abandoned, young child whose parents became lost during the disaster, into his life. Taking care of Anette becomes his main occupation. Among other characters of the book, there is Egemon, who is elected the king of street cleaners, beaten to pieces by angry taxi drivers and whom the doctors sew together again. Madam Donna, who in a strange metaphysical way resembles Anette, offers accommodation to two dead men under the floor of her hut. The bodies are a Jew, Sholem, who was killed at a concentration camp and his one time prison guard Rainer. At the end of the book, Anette’s parents find her and take her away. Varblane is alone again and sad. The existence of the girl is only confirmed by a heap of paper sheets, where 754 times she had started a letter to him with the words DEAR VARBLANE, but hadn’t known how to continue.

The critics have quite unanimously found that Kivastik’s Sparrow has features in common with Astrid Lindgren, Charles Dickens and Roald Dahl. They have referred to it as “literature for the whole family”. Although its humour is tar black now and then, the pathos of this seemingly unpretentious, but fairy-tale like story is very humane and full of the hope of breaking away from the rubbish-filled, low world into a new, better one.

Jüri Ehlvest. Elli’s Flight (Elli lend)

Tallinn: “”Loomingu” Raamatukogu”, 1999/9. 55 pp

“When beaten, it is entirely another subject than when it has only been passed through.” This sentence is repeated many times in Jüri Ehlvest’s longer short story “Elli lend”. The beating of subject matter at hand (just like beating the white and yolk of an egg into a mixture) could be the peculiarity of Ehlvest’s text-making. Passing through a subject is studying it in the sense of doing homework, just like solving a math problem or learning some historical dates by heart. Beating, in Ehlvest’s sense, means stirring up different layers of text, mixing up different stories told in this text, and then adding numerous evasions and interruptions to it. Ehlvest is obviously interested in occultism and esotericism, which he generously incorporates into his texts. He also makes fun of his readers and continually evades them. It is clear why he allows the press to place the epithet “a complicated writer” in front of his name. In Elli’s Flight, Ehlvest quotes Vaino Vahing, the most remarkable representative of the Estonian psychoanalytical school: “Say whatever comes to your head, don’t care, whether anybody understands you or not, the main thing is, you have to believe that you understand yourself, then you are a writer.” He adopts this quote as his self-ironical credo.

The motif of beating arises in Elli’s Flight in connection with the seventeenth-century England dish “hot chicken”. It was prepared from an egg that was boiled for three minutes, then cut into two, mixed with butter, melted cheese and herbs and then eaten straight from the shell. In closer reading, the two main layers of text resemble halves of an egg. First, it is a love story; the fragile and broken plot describes the story of the main character Elli’s adultery. Aulis, whom she desires, cannot tolerate girls who smoke, and when in the finale of the book a cigarette, known as a vulgar-Freudist symbol, emerges from his pants instead of a penis, Elli becomes confused. The other layer describes the author’s efforts in getting into Elli’s psyche and discovering her intentions. He shapes her into a character using her lecture notes on some theological subject as his starting point. In addition (just like herbs in the dish), a third layer can be distinguished in the book which, like an essay, embodies discussions about the fictionality of literature and creation psychology. The title of the book originates from these musings. At the end of the book, Ehlvest quotes the words of Plotinos about moving towards Good and about spiritual development. Parodically, such development, enlightenment and growing ease is illustrated by tobacco smoke. When Elli inhales it like a gas it is as if she launches into flight. Alternatively, it may be a metaphysical, blissful moment of swallowing sperm that lifts Elli off the ground. There is still another possibility. Flammable gas may leak out as the confused Elli is about to light the cigarette that extends from Aulis’s pants and this sends her flying.

Ehlvest’s text, which has been constructed according to the canon of postmodernism, is foremost a game; Ehlvest plays with the reader and fully enjoys it. Unlike in Eco’s The Name of the Rose, in Ehlvest’s Elli’s Flight one can not understand, even in the end, whether it is an absurd joke or a serious work which demands repeated rereading to get to its core. The reader is left to wander in the labyrinth of his text, just like his characters often do, face strange and unanswerable questions. Ehlvest himself is equally good, however, in making things clear and in making them confused, in asking riddles and in hiding the answers.

Short overviews of books by Estonian authors

By Rutt Hinrikus and Janiks Kronberg

–

Share: